“If you want to be a millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline.” - Richard Branson

Globally, aviation has always been considered a tough business.

In India, it goes a step further.

For decades, Indian aviation carried a brutal reputation of living up to this quote. It is a business where demand always existed, but profits almost never did.

Warren Buffett once famously said that if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he should have shot down the first airplane. Indian aviation, for decades, seemed to prove him right.

Why?

Well, the economics were stacked against airlines from the start here.

In India, it is among the most heavily taxed in the world.

And guess what? Fuel alone may account for 45-60% of an airline’s operating costs. So whenever global oil prices rise, Indian airlines feel the impact far more sharply than their global peers.

Add to that currency risk. Indian airlines earn revenue in rupees but pay for aircraft leases, engines, maintenance, and spare parts in US dollars. Every time the rupee weakens, costs quietly rise and margins get squeezed.

Then comes government policy. Jet fuel sits outside the GST framework, which means airlines pay high taxes but cannot claim input credits on their single largest cost. At the same time, airport charges, landing fees, and navigation costs keep climbing.

And all of this plays out in a country where passengers are extremely price-sensitive.

This is exactly why, over time, the list of casualties in the industry kept growing.

- Kingfisher Airlines collapsed under debt and unpaid salaries.

- Jet Airways shut down after years of financial stress.

- Air India survived, but only because the government kept writing cheques for decades, absorbing losses that ran into tens of thousands of crores.

In fact, more than 25 Indian airlines have shut down since liberalisation.

The narrative is that at best, they barely survive. At worst, they implode.

And then, something changed.

In FY24, IndiGo, officially InterGlobe Aviation, reported a net profit of Rs 8,172 crore, becoming the first Indian airline in history to cross the billion-dollar profit mark.

Just one year earlier, it had reported a loss of Rs 306 crore.

For an industry written off as structurally broken, this was a shock.

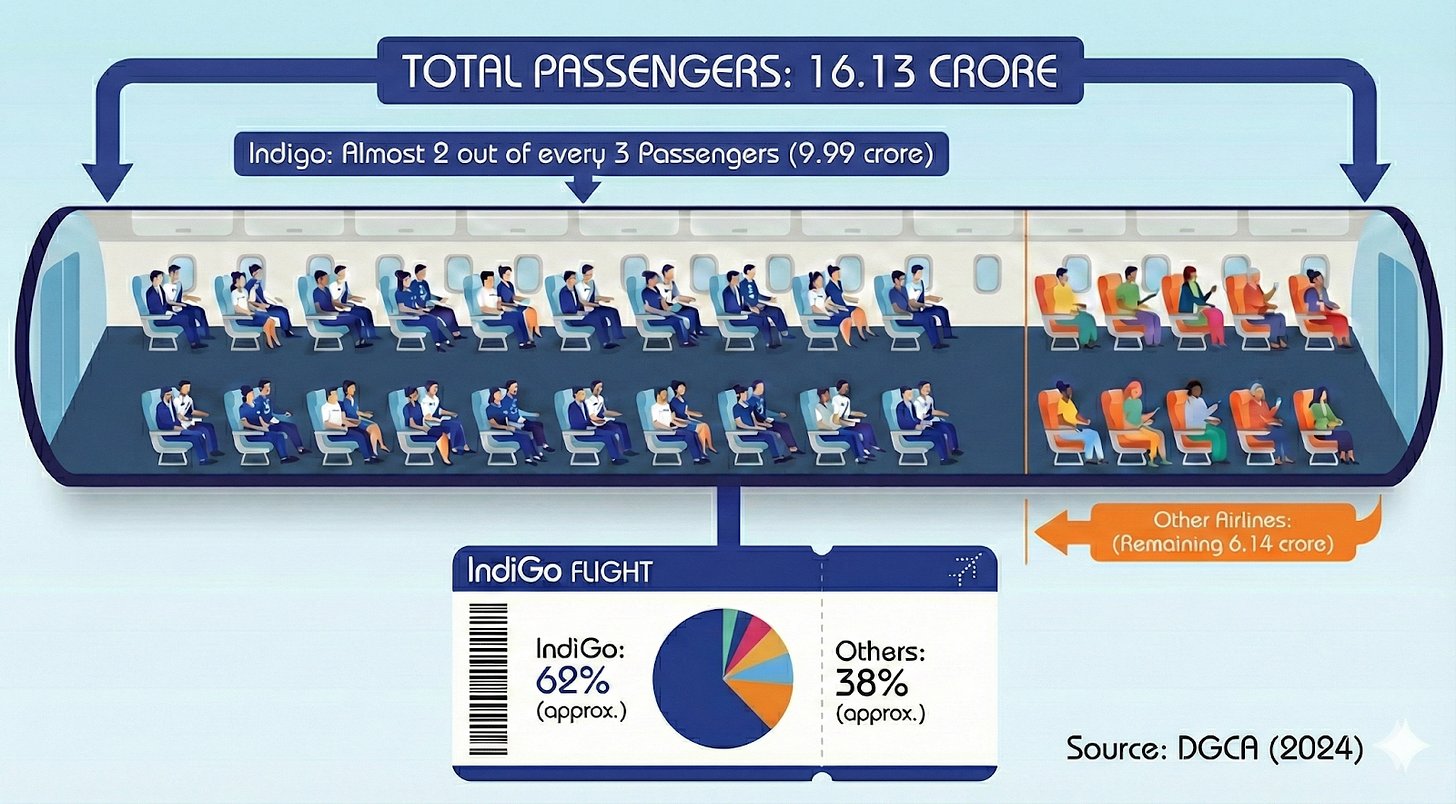

IndiGo wasn’t just profitable. It was dominant. With a market share of around 60-65%, it carried more passengers than any airline in the country by a huge margin. In many cities, most flights on the departure board were just IndiGo flights.

In a single year, around 10 crore passengers flew IndiGo. Put simply, nearly 2 out of every 3 people who flew within India that year were on an IndiGo aircraft.

This didn’t happen by chance.

This report explores how IndiGo quietly built a competitive advantage that other airlines have struggled to replicate and why, even when they try, it is so difficult to build the same advantage.

Low-cost Operating System

Most airlines fail because costs remain high while ticket prices are forced down.

In India, this pressure is extreme. Fares are among the lowest in the world, while fuel, taxes, and infrastructure costs remain stubbornly high.

IndiGo recognised early that survival in this market required more than calling itself a low-cost airline. It had to be the lowest-cost airline per seat, structurally and consistently, not just in branding.

From the day it launched in 2006, IndiGo didn’t try to cut costs later. It designed the airline to be low-cost from the start. The operating model was built to remove complexity at every layer and to keep costs low even as the airline scaled.

That system rested on 3 structural choices:

- Fleet simplicity

IndiGo chose to fly almost one type of aircraft.

Most of IndiGo’s planes are Airbus A320 aircraft, which are the standard jets used on most domestic flights.

For very short routes and smaller cities, it also uses a few smaller propeller planes that are cheaper to fly and can operate from shorter runways.

Using the same kind of aircraft made everything cheaper and easier — pilots needed less training, maintenance was simpler, fewer spare parts were required, and scheduling planes and crews became smoother.

Airlines that fly many different types of planes carry these extra costs all the time, and the problem only gets worse as they grow.

- Feet youth and fuel efficiency

Fuel is the biggest expense for any airline. IndiGo tackled this by keeping its planes new and switching early to newer Airbus models like the A320neo and A321neo, which burn about 15% less fuel than older aircraft.

Newer planes also fit more seats. IndiGo’s A320s carry around 180-186 passengers, and its larger A321neos carry about 222 passengers.

More seats on each flight meant the same costs were spread across more people, keeping the cost per passenger low.

- Utilisation discipline

An aircraft earns money only when it is in the air. IndiGo made sure its planes spent as little time on the ground as possible. Turnarounds were kept to 20-25 minutes, and each aircraft flew 12-13 hours a day, compared to 8-10 hours for many competitors.

Flying more every day meant each plane generated more revenue, and the cost of owning and operating it was spread across more flights and passengers.

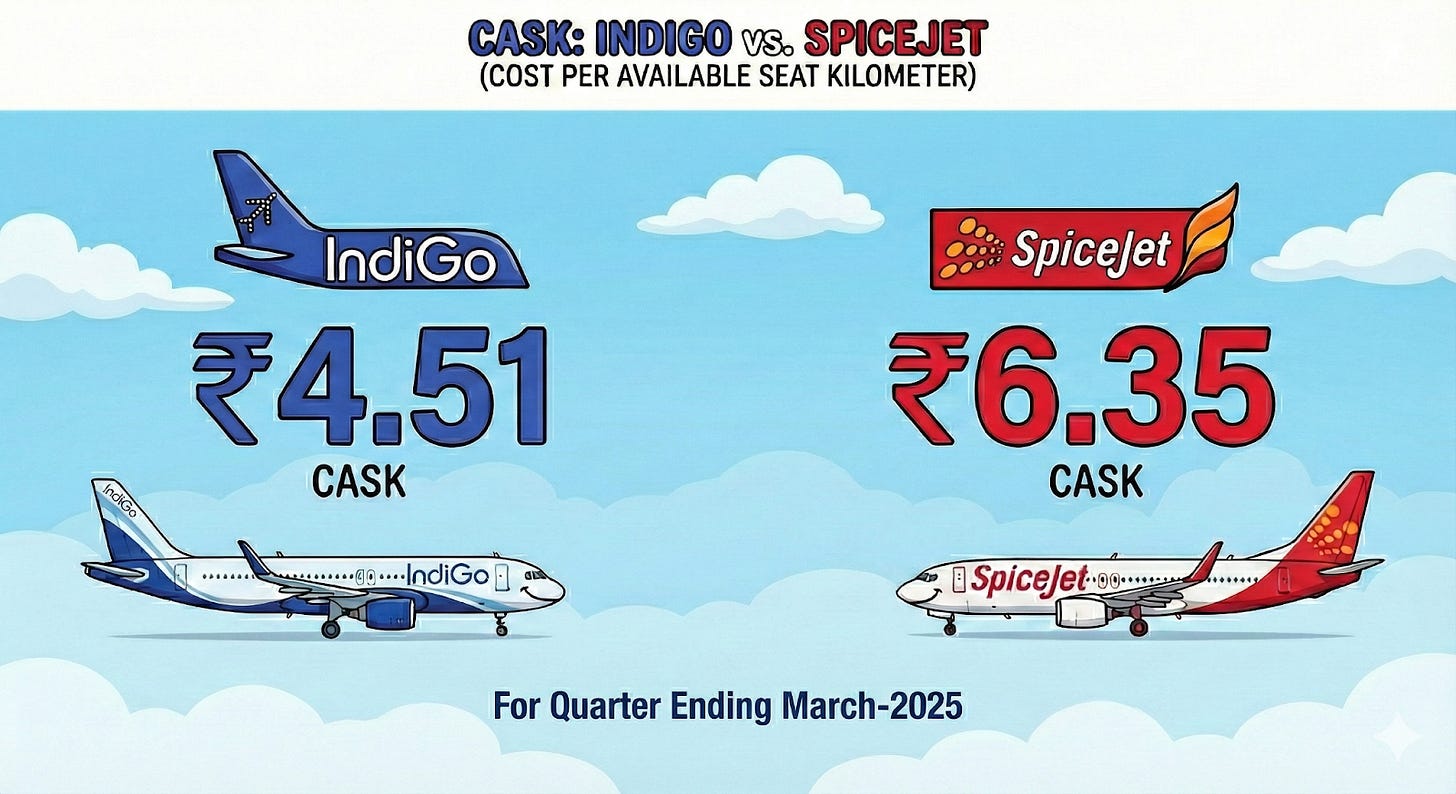

This showed up clearly in the most important airline cost metric: CASK (Cost per Available Seat Kilometre).

By the end of FY25, IndiGo’s total CASK was about Rs 4.51 per km, while SpiceJet’s was around Rs 6.35 per km. That is roughly 25% higher.

If you remove fuel costs, the difference was even bigger. IndiGo’s cost was about Rs 2.90 per km, compared to Rs 4.41 per km for SpiceJet . That’s almost a 30% cost advantage.

This low-cost model became IndiGo’s core moat.

It allowed the airline to survive fare wars, fuel price spikes, and periods when travel demand slowed.

But low costs alone don’t explain how IndiGo grew so fast and so aggressively.

For that, the way the company raised and used capital mattered just as much.

Sale-and-leaseback

For most airlines, buying aircraft puts pressure on the balance sheet. Each new plane needs a lot of upfront money, usually borrowed, and that debt has to be paid back over many years. When demand falls or costs rise, this pressure becomes painful very quickly.

IndiGo handled aircraft ownership very differently.

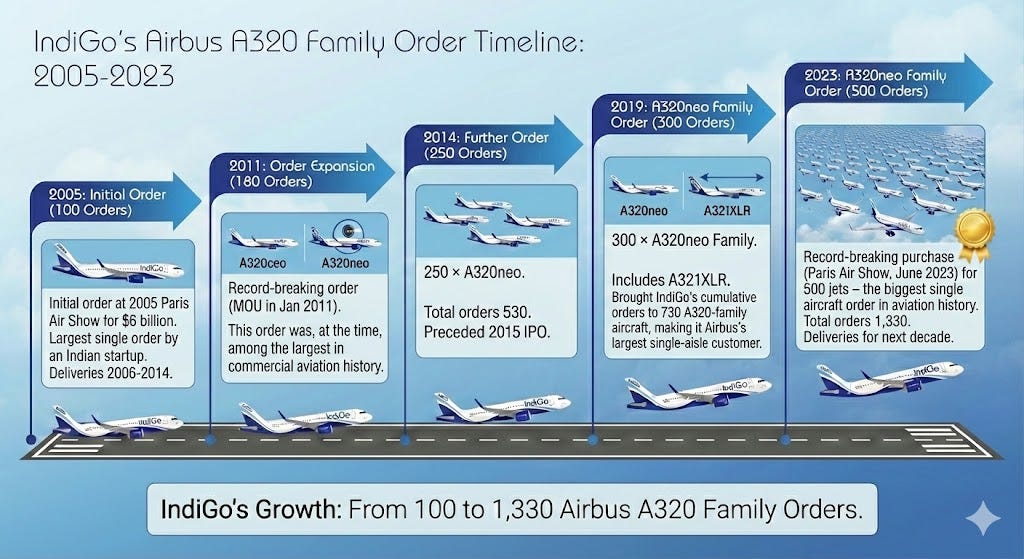

From early on, it placed aircraft orders at a scale few Indian airlines could match. Over the years, these orders kept getting bigger — 100 aircraft in 2005, 180 in 2011, 250 in 2014, 300 in 2019, and 500 in 2023.

This created a pipeline of around 1,330 aircraft, one of the largest order books in global aviation.

That scale gave IndiGo two big advantages.

Aircraft pricing power.

The official list price of an Airbus A320neo runs well above $100 million, but in aviation these prices are mostly symbolic. Airlines that place large, repeat orders usually negotiate steep discounts — often 40-60% off list price.

IndiGo was in an unusually strong position. It became Airbus’s largest customer for the A320 family worldwide, placing massive orders and sticking to a single aircraft type.

Industry analysts have long suggested that this allowed IndiGo to buy planes at prices far below catalogue levels. While exact numbers aren’t public, the broad consensus is clear: IndiGo paid meaningfully less per aircraft than smaller or less committed airlines could ever achieve.

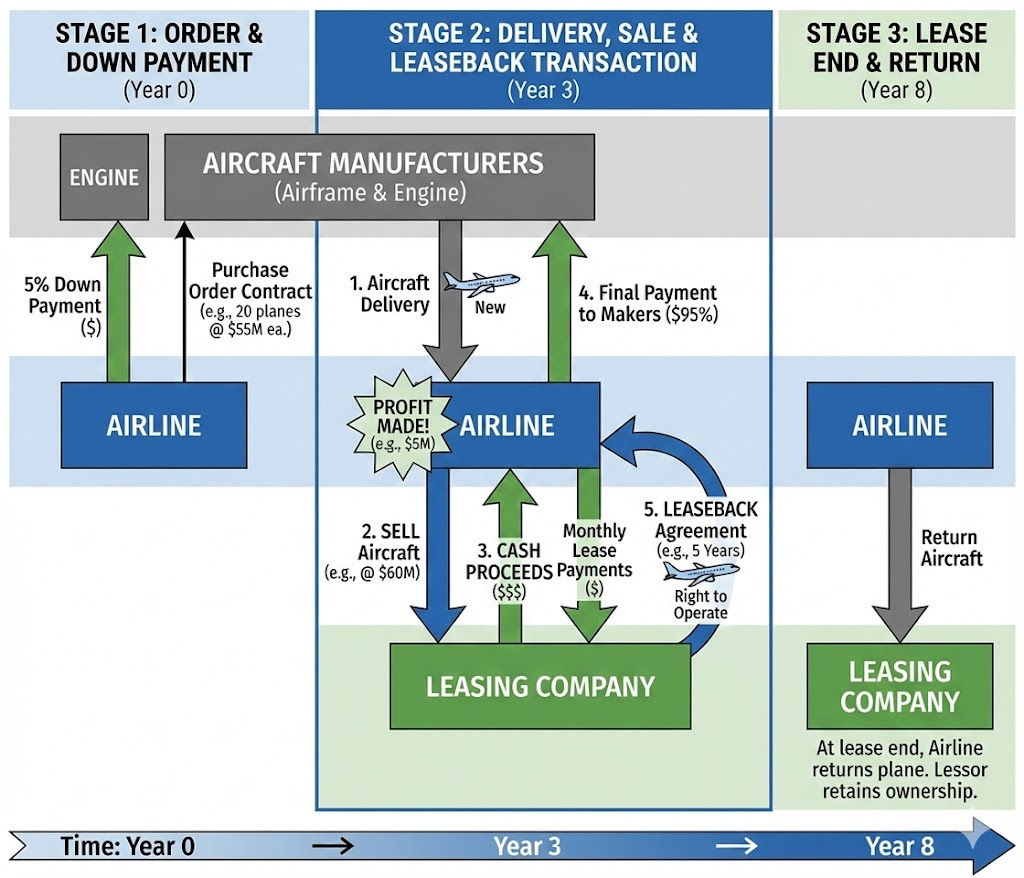

Monetising aircraft deliveries through sale-and-leasebacks.

IndiGo never planned to own most of its planes for the long term. Instead, it regularly used a sale-and-leaseback model. When a new aircraft arrived from Airbus, IndiGo would usually sell it almost immediately to a leasing company and then lease the same aircraft back to fly.

Its partners included some of the world’s largest aircraft lessors such as AerCap, Avolon, SMBC Aviation Capital, BOC Aviation, Air Lease Corporation, DAE, and ICBC Leasing, reflecting both IndiGo’s scale and its strong credit profile.

Because IndiGo bought aircraft cheaply and sold them at market prices, each delivery often generated upfront cash.

In strong leasing markets, these sale-and-leaseback deals across the industry have been known to produce meaningful one-time gains per aircraft. This improved liquidity and reduced the need to raise equity or take on heavy debt.

Together, lower aircraft costs and disciplined use of sale-and-leasebacks strengthened IndiGo’s cost advantage and turned scale into lasting financial resilience.

This changed how growth worked for IndiGo. Instead of new aircraft locking up capital, adding planes often freed up cash.

That money could then be used across the business to run day-to-day operations, absorb shocks like fuel spikes or downturns, or support even more growth, without depending heavily on debt.

The real value of this structure showed up during industry stress.

During the 2008 oil price spike, IndiGo stayed close to break-even while many airlines struggled.

After Kingfisher collapsed in 2012, IndiGo expanded quickly and filled the gap left behind.

When Jet Airways failed in 2019, IndiGo absorbed capacity almost immediately. It then placed a 300-aircraft order, pushing its market share beyond 47%, which later climbed toward 63%.

During COVID-19, while much of the industry was fighting for survival, IndiGo maintained strong liquidity — raising Rs 6,600 crore in FY21 and planning another Rs 4,500 crore in FY22.

By FY24, IndiGo had Rs 34,737 crore in cash, only Rs 7,800 crore in borrowings, lease liabilities of Rs 43,488 crore, and an EBITDAR margin of 25.5%.

At this point, growth was funding itself.

Delivery-slot dominance (when time itself became the moat)

Aircraft manufacturing doesn’t move fast. Airbus and Boeing can produce only a fixed number of planes each year, and when demand is strong, delivery backlogs stretch 8 years to 10 years into the future. Once delivery slots are taken, more aircraft simply can’t be added quickly.

IndiGo understood this constraint and used it to its advantage.

While other airlines were focused on surviving the short term, IndiGo focused on getting in early. The aim wasn’t just to grow but to lock in certainty.

By committing ahead of time, IndiGo made sure new aircraft would arrive exactly when demand returned, not years later.

When domestic air travel bounced back after COVID, the difference became obvious. IndiGo had new aircraft arriving on time. Many rivals did not.

Some airlines faced delivery delays, some struggled to add planes, and others had parts of their fleets grounded.

Each time an airline exited the market (Kingfisher in 2012, Jet Airways in 2019, and Go First in 2023), IndiGo was able to step in immediately. It absorbed routes, airport slots, and passenger demand because aircraft were already available.

Other airlines couldn’t react fast enough. The problem was they didn’t have planes.

Over time, this turned into a lasting fleet advantage.

By the mid-2020s, IndiGo had one of the youngest aircraft fleets in the world. The average plane was less than four years old, and most of the fleet consisted of A320neo and A321neo aircraft.

Newer aircraft break down less, face fewer technical issues, and can fly more hours each day.

In a demanding market like India, that reliability adds up, and over time, reliability compounds into scale.

This is why IndiGo’s delivery-slot advantage is really a time moat, not a pricing one.

It can’t be recreated today. Ordering aircraft now won’t deliver planes for most of this decade.

The delivery positions that allowed IndiGo to grow this much were locked in many years earlier.

By then, the advantage had become permanent.

Keeping costs low made IndiGo financially strong. That strength gave it time. And in an industry where planes are scarce, time turned into a permanent advantage.

You can’t build this moat by raising money today. You had to be early.

Scale and network density (the structural market moat)

This is the moat most people notice first (packed departure boards, high flight frequency, and a dominant market share). But the direction of causality matters.

Scale did not create IndiGo’s advantage. Scale was the result of it. In aviation, airlines that grow big without low costs usually don’t survive for long.

By the mid-2020s, IndiGo was operating close to 1,800 flights a day, serving 90+ domestic destinations, and carrying 100+ million passengers each year.

Its domestic market share grew from about 9% in 2007 to around 37% by 2015 and then to around 60-65% by FY25.

That scale unlocked something more durable than size alone. Thats network density.

IndiGo started flying to places frequently. On major routes, it often ran the most flights each day, which made it the easiest choice even if fares were slightly higher or lower.

By 2025, IndiGo operated around 900 domestic routes (that’s nearly 80% of all active domestic sectors in India). Of these, it was the sole operator on 514 routes, meaning over 57% of IndiGo’s network had no competing airline at all.

This is often described as an “IndiGo monopoly”, but the word needs context. Many of these routes connect tier-2 and tier-3 cities, smaller airports, and low-density markets where operating economics are difficult.

Other airlines either cannot make these routes profitable or lack the scale to sustain them. Without IndiGo, large parts of India would simply lose regular air connectivity.

Monopoly routes are not unique to IndiGo. Regional airlines like Alliance Air, Star Air, IndiaOne, and Fly91 also operate a high share of monopoly sectors.

In fact, out of roughly 1,131 domestic routes in India, about 70% are served by a single airline. IndiGo dominates this structure because it operates at a national scale, not because the structure itself is unusual.

Where competition does exist, it is concentrated. India has about 249 duopoly routes, mostly between major cities. IndiGo competes most often with Air India Express and Air India on these sectors. Only a handful of routes exist where IndiGo is entirely absent.

This created a barrier that competitors found hard to break.

Prices can always be cut. Frequency and connectivity cannot be built overnight.

Network density also gave IndiGo an edge at crowded airports. At hubs like Delhi and Mumbai, airport capacity grows slowly, and takeoff and landing slots are limited. Over time, IndiGo captured a large share of the most valuable slots.

Morning and evening slots matter the most. They attract business travellers and tend to fly fuller. Once an airline locks in these slots, they are very hard to take away.

New airlines can still add flights, but often only at inconvenient hours. Those flights are harder to fill and less profitable.

Scale reinforced yet another advantage: bargaining power. With a fleet of 400+ aircraft and one of the largest Airbus order books in the world, IndiGo could negotiate better terms with airports, maintenance firms, lessors, and other suppliers.

IndiGo’s scale pushed costs per seat lower, while smaller airlines were stuck with higher per-aircraft costs, weaker supplier leverage, and not much ability to absorb shocks..

That order of events mattered.

Once IndiGo crossed a certain scale, the business began to protect itself. Competition was no longer airline versus airline — it became airline versus network.

And once a network becomes dense enough, it is extremely hard to break.

Hats off to the team who are writing these articles. :D

It's great to plan such a strategy and carryout the same successfully. A Himalyan Task - hats off Indego !