In the late 1920s, J.P. Morgan did something no financial institution had done before.

They introduced a new instrument, a depositary receipt on the New York Curb Exchange — the predecessor of today’s American Stock Exchange.

That receipt represented shares of a British company, Selfridges, held in custody in the UK.

It was denominated in US dollars and acted like a US stock.

This was the world’s first American Depository Receipt, aka ADR.

For the first time, US investors could own an economic interest in a foreign company through a US-traded security, without touching a foreign currency.

For years, ADRs remained a niche idea. But regulators soon saw the opportunity.

In the 1950s, the SEC (basically the SEBI of the US) formalised ADR rules.

This regulatory clarity transformed ADRs from a niche idea into a credible global structure.

Decades later, ADRs are everywhere.

Even Indian companies like HDFC Bank, Infosys, ICICI Bank, Wipro, and Dr Reddy’s all trade in the US through ADRs.

But this convenience has also created a doubt for investors sitting in India.

Since they trade when Indian markets are closed. They are priced in US Dollar, not Indian Rupee. They react to US macro news, global risk sentiment, and currency movements.

So it feels natural to think that investing via ADRs might give you a very different outcome than buying the same stock in India.

Some even look at ADR prices to guess how those stocks will open in the Indian markets the next day.

Which raises an important question.

If ADRs are listed in the US, priced in dollars, and traded in a different market, do they actually deliver different returns from the same stock listed in India?

We did an experiment to find out…

The experiment

We picked five Indian companies that have been listed both in India and in the US as ADRs for a long time:

HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, Infosys, Wipro, and Dr Reddy’s.

For each company, we collected three sets of real-world data:

- NSE-listed stock prices (in rupees)

- ADR prices (in US dollars)

- USD/INR exchange rate for the same dates

To keep the comparison fair and clean, we used only dates where all three prices existed together.

From 6 January 2010 to 31 December 2025

What we saw at first (and why it looks alarming)

When we calculated long-term returns the usual way, Indian-listed stocks showed strong compounding in rupees, and ADRs showed lower returns in dollars.

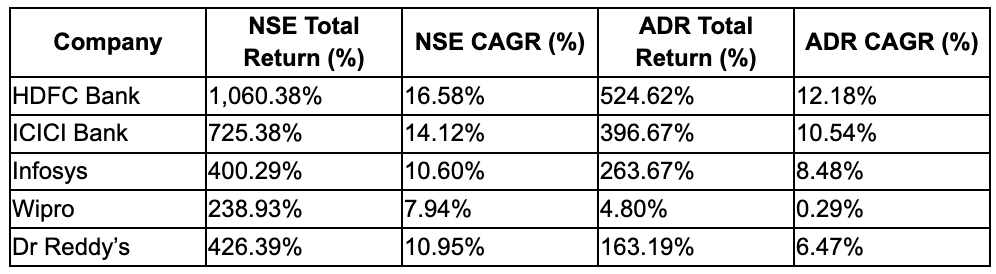

Total Returns Comparison (2010–2025)

You can see that ADRs clearly underperform compared to an investor investing in India.

Here’s the part that changes everything.

Indian companies earn profits in rupees, and the stock prices are in rupees so the returns are calculated in rupees.

But ADR prices are in dollars.

Here, it is important to note here that over the last 15 years, the rupee steadily lost value against the dollar. That depreciation quietly eats into dollar-denominated returns, even when the stocks showing returns in the Indian markets are doing well.

So when you compare, one return is being measured in a currency that weakened over time; the other is being measured in the currency that strengthened.

Without adjusting for it, you’re not comparing true performance.

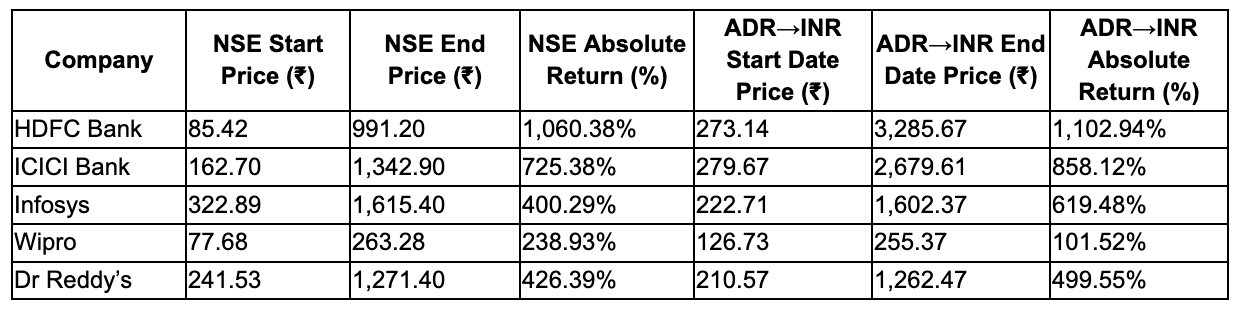

Once you convert ADR prices back into rupees, the picture becomes very clear.

For every trading day in our dataset, the ADR price in dollars was multiplied by the USD/INR rate of that same day.

This gave us an “ADR-in-rupees” price series that could be compared directly with the NSE stock price, date for date.

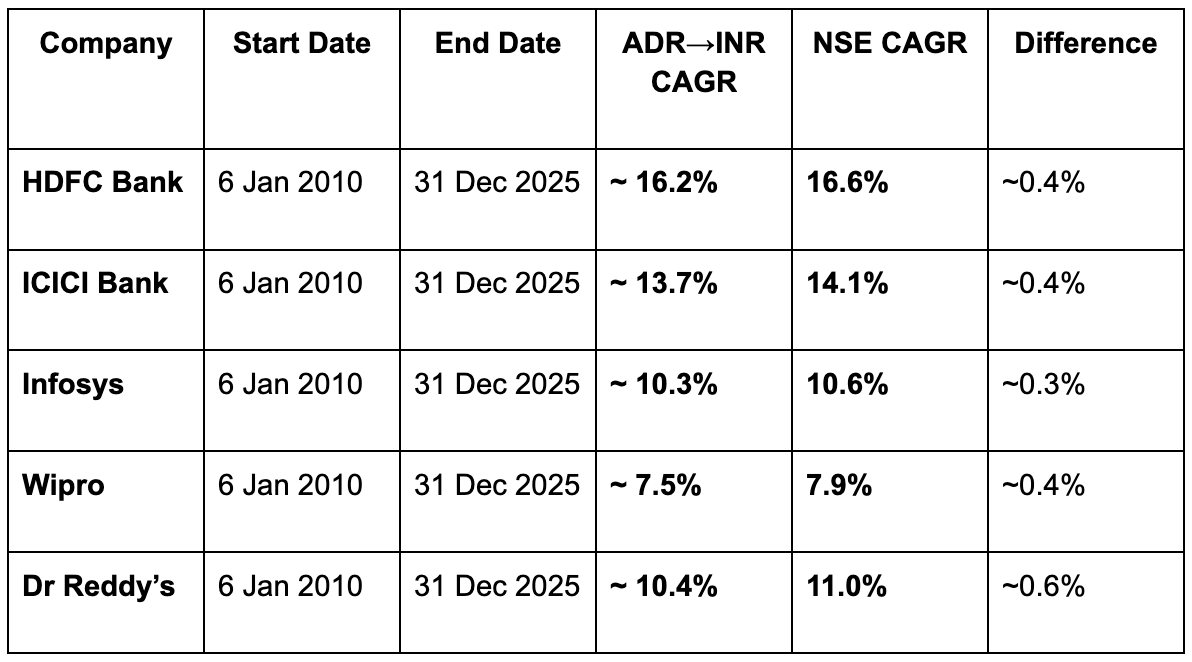

When we then calculated 15-year returns from 6 January 2010 to 31 December 2025, the ADR-to-INR returns were almost identical to NSE returns across all companies.

HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, Infosys, Dr Reddy’s — the CAGR difference was typically less than half a percent.

(These small gaps came from mechanical factors like ADR ratios, dividend timing, and different holiday calendars, not from any meaningful economic divergence.)

The real insight we get from this is that ADRs were never underperforming.

They were simply showing Indian stock performance after currency translation.

Dollar returns look lower mainly because the rupee has depreciated over time.

An ADR is not a separate company or a different bet. It is the same Indian stock, held by a US bank, and represented as a receipt that trades in the US.

The company is the same. The shares are the same. The business risks are the same. The only difference is where and in which currency the stock is being shown.

When an Indian company creates an ADR, a US bank (called a depository bank) buys the company’s shares in India and holds them with a local custodian. Against those shares, the bank issues ADRs in the US market. Each ADR represents a pre-decided ratio of Indian shares.

For example:

- 1 ADR might represent 2 Indian shares

- Or 1 ADR might represent 10 Indian shares

- Sometimes it’s even a fraction, like ½ a share

This ratio is set so that the ADR price stays in a sensible range for US investors.

If ADRs don’t change returns, why do they exist at all?

Because they solve an access problem, not a performance problem.

For a global investor, buying shares directly in India involves foreign accounts, local regulations, custody arrangements, tax complexity, and currency conversion. ADRs remove all that friction.

They let global investors buy Indian companies as easily as buying US stock — in dollars, on US exchanges, through familiar systems.

For Indian companies, ADRs expand the investor base. They bring in global capital, improve visibility, and increase liquidity without changing the underlying business.

ADRs are not designed to outperform or underperform. They exist to connect markets, making the same stock investable across borders.