In 1960, Warren Buffett bought a struggling textile mill in Massachusetts called Berkshire Hathaway.

He turned this company into a holding company — a company that doesn’t make products but owns shares or entire businesses.

Under Berkshire’s name, Buffett started buying profitable companies like GEICO (insurance), Coca-Cola, American Express, etc.

Over time, Berkshire Hathaway became one of the most valuable companies in the world.

But here’s the twist — it doesn’t pay a single dollar in dividends. Not once, in over 50 years.

And yet, Buffett himself earns billions every year from dividends — through the companies he owns.

That’s the paradox of investing.

The world’s greatest investor earns from dividends yet believes that the best companies are those that reinvest profits back into growth instead of giving them away.

When it comes to investing, everyone loves the idea of passive income. After all, who doesn’t enjoy getting that sweet dividend alert in their inbox?

It sounds so simple — buy the stocks that keep paying you regularly.

More dividends mean more money, right?

But here’s where things get tricky. There’s also the belief that dividend stocks may give you steady income but lower long-term returns, while growth stocks, which don’t pay dividends, often deliver higher returns because they reinvest their profits back into the business.

That leaves investors stuck in a dilemma.

Does one go for the steady dividend payers — companies that distribute profits year after year?

Or does one prefer the growth companies — the ones that reinvest earnings back into their business instead of paying shareholders?

The popular belief is that dividend stocks offer good payouts but slower growth, while growth stocks skip the payouts but deliver bigger long-term returns.

But how much of that is actually true? What is the reason behind it?

We decided to find out.

We wanted to compare long-term returns between two opposite investing styles:

Companies that consistently pay high dividends — the income-oriented stocks.

Companies that pay little or no dividends — the growth-oriented stocks.

And within the high-dividend group, there could be two kinds of investors

Investor A: Reinvests every dividend back into the same stock (total return).

Investor B: Takes the dividend as cash every time it is paid out and uses it for their own use.

Our analysis had to start with picking the stocks that give high dividends and little/no dividends

We started with Nifty 200 and looked for their last 10 years of data. All the recently listed or new-age companies without 10-year data were excluded.

To keep everything consistent, we used the same time frame for every company — FY2015-16 to FY2024-25. That gave us a decade-long window, covering both bull markets and bear markets — ideal for testing long-term patterns.

Next, we looked at each company’s dividend yield — the ratio of annual dividend to the share price.

Dividend yield is calculated as the total dividend paid in a year divided by the stock’s current market price, expressed as a percentage.

In simple terms, it tells you how much income you earn each year for every Rs 100 invested in that stock.

We identified companies that consistently gave high dividends year after year and those that paid little to none throughout the period.

From this exercise, we picked two clear extremes. The top ten regular high-dividend payers and the bottom ten companies that rarely or never distributed dividends.

Top 10 (High-Dividend Group): Vedanta, Coal India, REC, Indian Oil (IOCL), Power Finance (PFC), NALCO, NMDC, Oracle Financial Services, Oil India, and BPCL.

These are classic high-yield names in the markets.

Bottom 10 (Low/No-Dividend Group): KEI Industries, Trent, Bajaj Finance, Solar Industries India, Bajaj Finserv, Cholamandalam Investment and Finance Company, Adani Power, The Phoenix Mills, Godrej Properties, and Titan Company.

In this list, we’ve included companies that not only pay little or no dividends but have also delivered the highest returns and strongest growth over the past decade.

These companies typically reinvest earnings into expansion rather than distributing them.

So we have three investors, starting with Rs 10 lakh each on 1 April 2015.

Investor A (The Reinvestor)

Buys the 10 high-dividend stocks.

Every time a dividend is paid, immediately uses that money to buy more shares of the same company on the ex-dividend date.

Fractional shares are allowed, so every rupee compounds over time.

Investor B (The Collector)

Buys the same 10 high-dividend stocks.

Takes each dividend payout as cash and keeps it aside — no reinvestment.

The portfolio’s value grows only through price changes, not through compounding.

And to benchmark them both, we track a third investor:

Investor C — The Growth Investor

Buys the 10 low- or zero-dividend stocks — the true growth companies that have shown the highest returns over the last decade.

These are companies that reinvest almost all their profits back into growth instead of paying shareholders.

No dividends, no payouts — just pure growth through the business itself.

All three start from the same point, and we track their portfolios over the next ten years.

At the end of this period, we calculated how much annualised return (CAGR) they achieved.

When you calculate that, you will find that...

The final comparison of the three distinct investment approaches doesn’t go along with common assumptions.

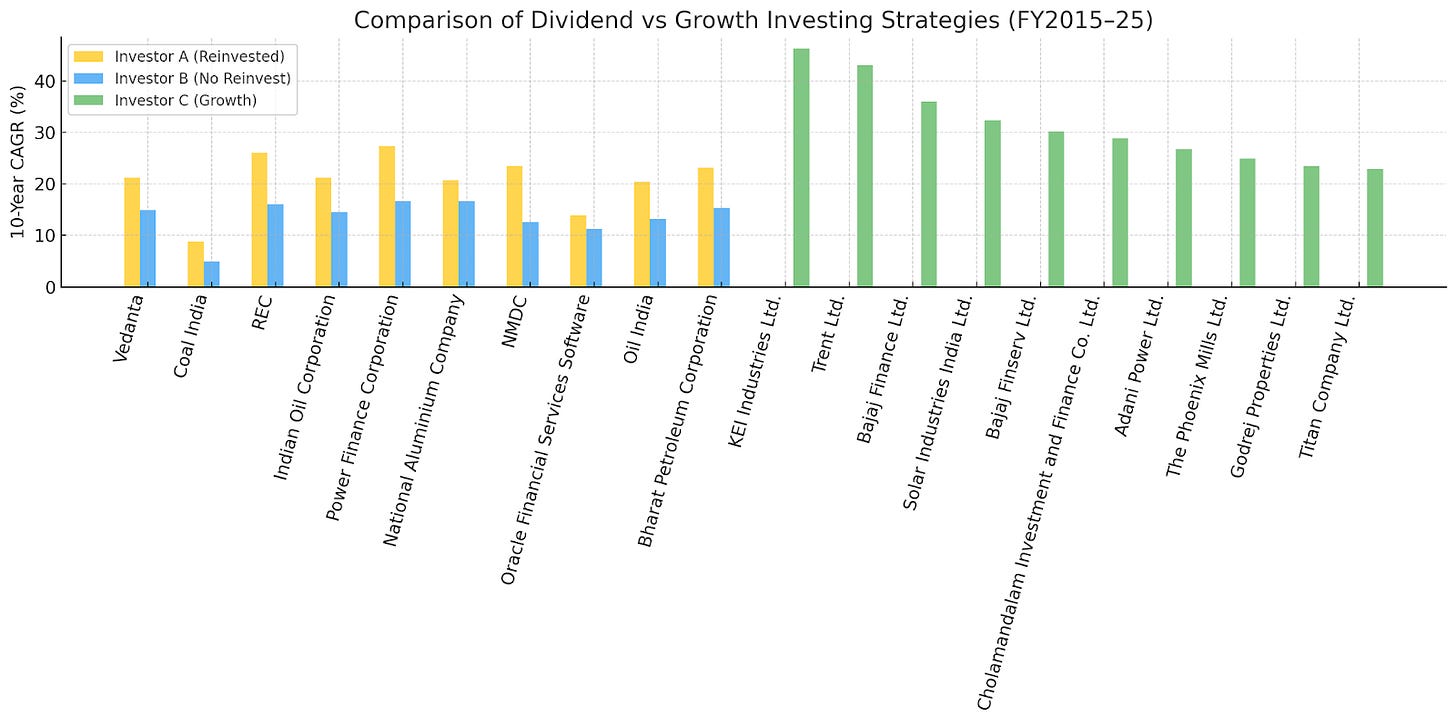

Plotting the 10-year CAGR (2015–2025) for all three approaches revealed some clear differences in how each strategy played out over time.

Results

On the chart:

Yellow bars represent Investor A — dividend investors who reinvested every payout.

Blue bars represent Investor B — dividend investors who took the dividends as cash.

Green bars represent Investor C — the growth-stock investors with little or no dividends.

The Reinvested Dividend Effect (Yellow Bars)

This is where the presence of compounding was quietly seen.

When dividends were reinvested, the high-yield stocks delivered strong annualised returns — mostly between 20% and 27% CAGR.

While this wasn’t as high as the top growth stocks, it came surprisingly close.

In other words, high-dividend stocks weren’t “slow” at all.

Once the dividends were reinvested, their total returns landed between the two extremes — much higher than the “no-reinvestment” approach, and not far behind the aggressive, low- or zero-dividend growth stocks.

Not Reinvesting the Dividend (Blue Bars)

This reflects what most investors actually do — collect dividends and either spend them or let the money sit idle.

It’s also the version of dividend investing that often gets criticised for “low growth”. And for good reason.

Without reinvestment, the same companies produced CAGRs between 8% and 15%, far below their reinvested versions.

Coal India dropped from 8.8% (reinvested) to barely 5% when dividends weren’t reinvested.

Vedanta shrank from 21.3% to 14.9% — a 6% annual drag simply because the dividends didn’t compound.

This blue bar pattern highlights a common misunderstanding: the idea that dividend-paying stocks underperform.

In reality, the issue isn’t the stocks themselves — it’s what investors do with the cash.

Once dividends are taken out of the compounding cycle, the power of growth slows dramatically.

The Growth-Stock Benchmark (Green Bars)

Now to the other side of the argument — the low- or zero-dividend companies.

In the top 10 highest returns givers here, the returns were in a range from 20% to 40%.

The average growth-stock CAGR was slightly above 30%, comfortably higher than the reinvested dividend group.

These are the companies that reinvest nearly every rupee of profit back into expansion, and the results can be seen in the data.

By keeping earnings within the business, they let the company itself do the compounding for shareholders.

But what’s interesting is how close the reinvested dividend group came to matching this performance.

When you line these three up visually, the difference is clear.

Reinvested dividends try to catch up with the returns of growth stocks — both deliver relatively higher long-term returns.

But the blue bars, where dividends are simply collected and not reinvested, sit much lower on the chart.

The data makes one thing clear: high-dividend stocks aren’t inherently slow-growth — they look that way when investors pull their dividends out and and let the money sit idle.

Reinvest those dividends, and over ten years the results are far better.

Skip reinvestment, and you may enjoy time to time income, but at the cost of long-term wealth creation.

At the same time, growth stocks, which rarely pay dividends, achieve even better outcomes by reinvesting earnings within the business.

So the next time you see a dividend credited to your account, remind yourself — dividends alone don’t make you rich; what you do with them does.

Whether it’s the company or the investor doing it, reinvestment is what drives real wealth in the long run.

Note:

While the analysis highlights the clear power of compounding and the long-term advantage of reinvesting dividends, it’s important to recognise the limitations of this simulation.

This model does not factor in taxes on dividends or capital gains, which in reality would slightly reduce the reinvested and final amounts for all investors.

Similarly, it assumes zero transaction costs—no brokerage, STT, or regulatory fees—whereas actual investing involves small but frequent costs, especially for Investor A who reinvests every payout.

The study also assumes the ability to buy fractional shares, ensuring that every rupee compounds without friction, but in practice, most Indian brokers don’t allow fractional equity purchases, leaving small uninvested cash balances that marginally lower returns.

Overall, while the results clearly show how reinvesting dividends can build long-term wealth, the actual returns in real life would probably be a bit lower because of things like taxes, trading costs, and other real-world factors.

Still, we made this report to give investors a broad, easy-to-understand comparison of how different investing styles work over time. Even with its limitations, it helps show one simple truth — whether it’s the investor or the company doing it, reinvestment is what truly drives long-term wealth creation.

This is genuinely one of the best empirical analyses of dividend investing I've ever read. The Buffett framing at the beginning is perfect - he earns billions from dividends yet refuses to pay them, which perfectly captures the paradox. Your data tells a powerful story: reinvested dividends delivered 20-27% CAGRs while the same stocks without reinvestment barely scraped 8-15%. That 12% annual drag from not compounding is absolutely massive over a decade. The yellow bars clustering close to the green bars is the most important chart here. It shows that when dividends are reinvested, the 'slow dividend payer' narrative completely falls apart. You're not far behind growth stocks at all - the gap is just 3-8% annualized, not 15-20% like many assume. The blue bars, however, tell a cautionary tale. Taking dividends as cash is actively harmful to wealth creation. It's essentially a forced distribution that creates taxable events and breaks the compounding chain. The disclaimer section is also appreciated - accounting for taxes and transaction costs would lower all three approaches slightly, but the relative rankings would likely stay the same. My only question is about survivorship bias - did you account for companies that went bust or got delisted during the 10-year period? Those would disproportionally affect the high-dividend group, which often includes cyclical and capital-intensive businesses. Regardles, this study confirms what Buffett has always said: it's not whether the company pays dividends that matters - it's what happens to the earnings, whether reinvested internally or externally. Exceptional work.

This comparison is Awesome and Beautiful. Kudos to your team for great efforts on researching this aspect. For common man who prefers MF over stocks It will also be helpful if similar analysis is presented about Mutual funds. Thanks once again for sincere, diligent and meticulously worked out article