Core Drivers of Gold (Historical Context)

Gold Cycles - A look into the history

Over the last century, gold has gone through several major price surges—often followed by periods of correction or stability. They’ve never been random and have almost always been triggered by a mix of four key factors, like we discussed earlier.

Geopolitical stress

Changes in monetary policy (especially interest rate shifts),

Sticky or rising inflation

De-dollarization— when countries move away from the US dollar and add more gold to their reserves.

These factors often overlap, but they don’t always act at the same time or with the same intensity.

In some periods, one of them clearly takes the lead, becoming the primary reason behind the rally — while the others play a supporting role.

Let’s look at specific time periods in history where gold prices surged. For each one, we’ll identify what triggered the move first, and how the other drivers followed.

Understanding this sequence not only explains the past — it also gives us a clearer image through which we can try to understand what might come next.

Early 1930s: The Great Depression

This was the first time gold saw a price surge in modern history; before this, gold was used as a standard.

The Great Depression began in 1929 and caused a massive economic crisis and global uncertainty. Industrial production plummeted by nearly 47% from 1929 to 1933, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average collapsed by almost 89% from its September 1929 peak (381.17) to its July 1932 low (41.22), wiping out large amounts of wealth in the economy and shattering public confidence.

As fear spread, people and investors started hoarding gold because it felt like a safe place to store their money. At the time, the U.S. was still on the gold standard, with the dollar officially pegged at $20.67 per ounce of gold. But this gold peg made things worse.

Because the dollar was tied to gold, the government couldn’t freely print more money or run big fiscal deficits to boost the economy. Prices began to fall sharply as a result.

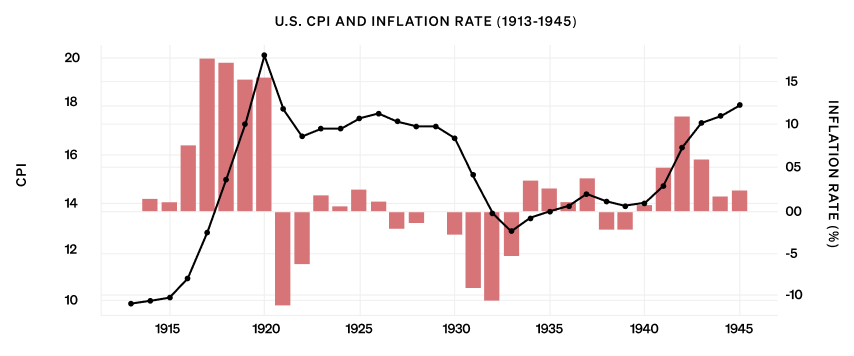

The U.S. experienced severe deflation — the Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped by 8.9% in 1931 and another 10.3% in 1932.

This growing distrust in the financial system led to a banking crisis, with nearly 9,000 out of 25,000 U.S. banks failing between 1930 and 1933. As the banking system collapsed and deflation deepened, the gold standard became unsustainable.

So, in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt took a bold step. He ended the gold standard, banned private ownership of gold, and devalued the U.S. dollar by raising the official gold price from $20.67 to $35/oz.

This effectively made the dollar worth nearly 65% less compared to gold.

Which meant, in practice, each dollar bought significantly less gold. This allowed the government to expand the money supply, fight deflation, and support the economy during the Great Depression.

The main driver was the geopolitical and economic crisis of the Great Depression, which forced a major monetary shift. The U.S. broke the dollar’s tie to gold and devalued its currency.

Here’s how it played out: first came the Depression itself with the crash, mass unemployment, and industrial collapse. This led to the policy response. The U.S. ended the gold peg, cut interest rates, and allowed the dollar to lose value. As a result, gold prices moved sharply higher.

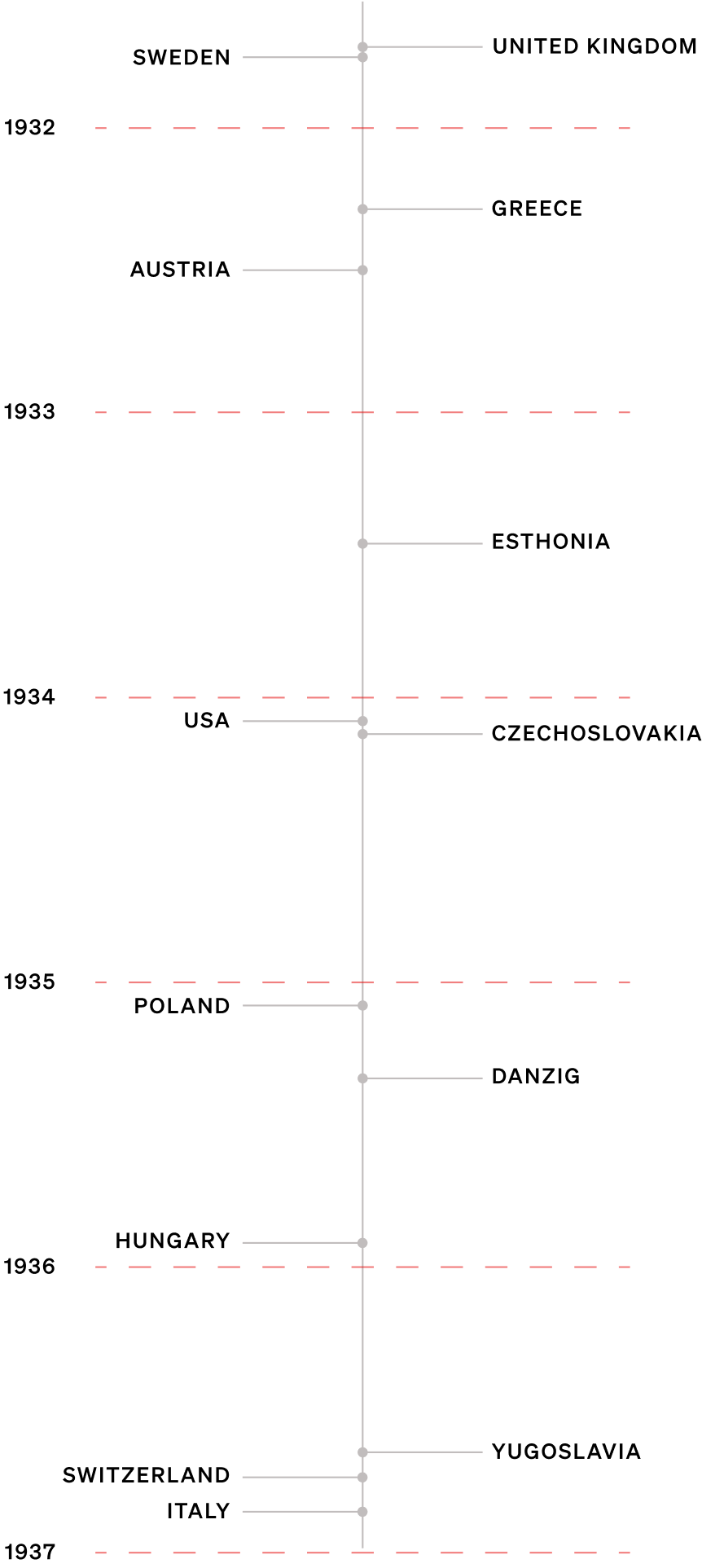

Soon after, other countries began to follow by abandoning their own gold pegs or devaluing their currencies. This sped up the global move away from a single gold-backed system

Main Driver: Economic crisis and currency policy change (end of the gold standard).

Followed by: Intentional currency devaluation (inflation) and the early phase of de-dollarization, as each country started running its own monetary policy.

Now let us look at the details of the sequence that cause the gold surge in the 1930s.

Interest Rate / Currency Policy Shift – Breaking from Gold:

At the time, the U.S. was stuck on the gold standard: each dollar was backed by gold, limiting how much money the government could print. This made it impossible to stimulate the economy — no room for deficit spending or monetary expansion. In 1933, President Roosevelt ended domestic gold convertibility — citizens could no longer exchange dollars for gold or legally own it in large amounts. Then in 1934, the U.S. officially raised the price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce — a 67% dollar devaluation. This allowed the government to print more dollars per ounce of gold, injecting more money into the economy. This was the turning point — it marked a clear policy break from past orthodoxy, giving rise to modern fiat monetary tools.Sticky or Rising Inflation— but not by accident:

After the dollar was devalued, the U.S. moved from deflation to mild, controlled inflation. The goal was to stop the price crash, encourage people to spend again, and restart economic activity. This was intentional reflation where policymakers wanted prices to rise just enough to bring wages and profits back up. Inflation was not yet a threat, but it was crucial for restoring confidence that growth could return. So while inflation was not the initial trigger, it was an important outcome that supported higher gold prices and a more flexible monetary environment.De-dollarization (Early Phase):

Once the U.S. abandoned the gold peg and devalued the dollar, other countries soon followed. The British pound had already left the gold peg in 1931 which initially made it weaker against the dollar. After the U.S. devaluation, the dollar’s value against the pound saw a significant shift. Other countries quickly followed. This marked the first true wave of global monetary divergence — where countries began to run independent monetary policies, not tied to gold or to each other. It wasn’t about rejecting the dollar yet, but it broke the shared gold standard system that had governed trade and currencies. This was the earliest version of de-dollarization: a move away from globally coordinated, gold-based money toward national control.

Timeline of Currency Devaluations During the Great Depression:

1970s–1980: Stagflation and Bretton Woods Collapse

The 1970s saw one of gold’s most dramatic bull markets.

Before 1971, gold was fixed at $35 per ounce. You could not freely buy or sell it since the U.S. government controlled the price because the dollar was tied to gold.

In 1971, the U.S. ended the Bretton Woods system (August 15, 1971, known as the “Nixon Shock”). After this, the dollar was no longer backed by gold, and gold was allowed to trade freely.

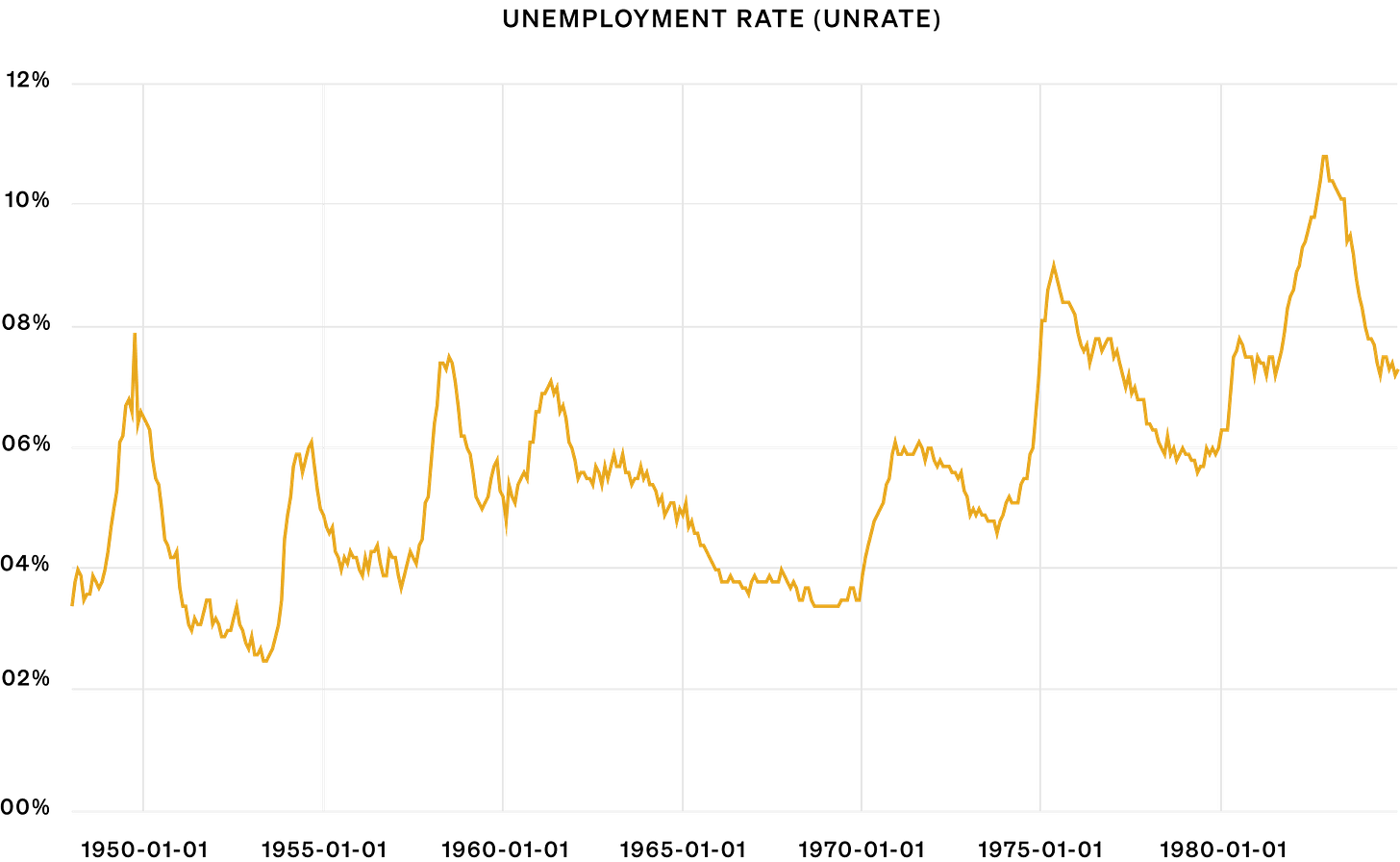

Around the same time, the U.S. faced stagflation, a rare and challenging combination of high inflation and high unemployment. Inflation hit double digits.

People lost faith in paper money like the U.S. dollar because it kept losing value. Gold, on the other hand, felt safer and more reliable.

As more and more people started buying gold, its price shot up fast.

It went from about $44.60 in 1971, after the peg was removed, to around $230 in early 1979. Then, within just a year, it soared to nearly $850 by January 1980.

The highest point came on January 21, 1980, at $850 per ounce — more than tripling in price, a massive 269% jump in such a short time.

Main Driver: Soaring inflation (stagflation) after the end of the gold-standard regime

Followed by: Geopolitical turmoil and a loss of confidence in the U.S. dollar (early de-dollarization trend).

Inflation and the End of the Gold Standard:

The U.S. printed too much money in the 1960s, with big government spending on the Vietnam War and social welfare programs without raising taxes. The economy was quietly slipping into an inflationary phase even before Bretton Woods collapsed.

In 1971, the U.S. ended the gold-dollar link (Bretton Woods System). The dollar was no longer backed by gold, allowing it to float freely and leading to its devaluation in the open market. This made people fear that the dollar’s purchasing power would keep falling

For context, the U.S. CPI (inflation rate) soared from 4.3 percent in 1971 to peak at 11.1 percent in 1974 and again at 13.5 percent in 1980. Concurrently, the unemployment rate climbed to 8.5 percent in 1975 and reached 7.8 percent in 1980, demonstrating the stagnation alongside inflation.

Real GDP growth was also volatile, with recessions in 1973–75 and 1980.

This combination of a broken monetary system and runaway inflation triggered a massive loss of confidence in paper money, and people turned to gold as a hedge. The breaking of the gold-dollar link and the onset of double-digit inflation formed the core reasons behind the 1970s gold boom.

Geopolitical turmoil:

During the 1970s, the world went through a series of major political and military crises that made investors even more nervous and pushed them toward gold.

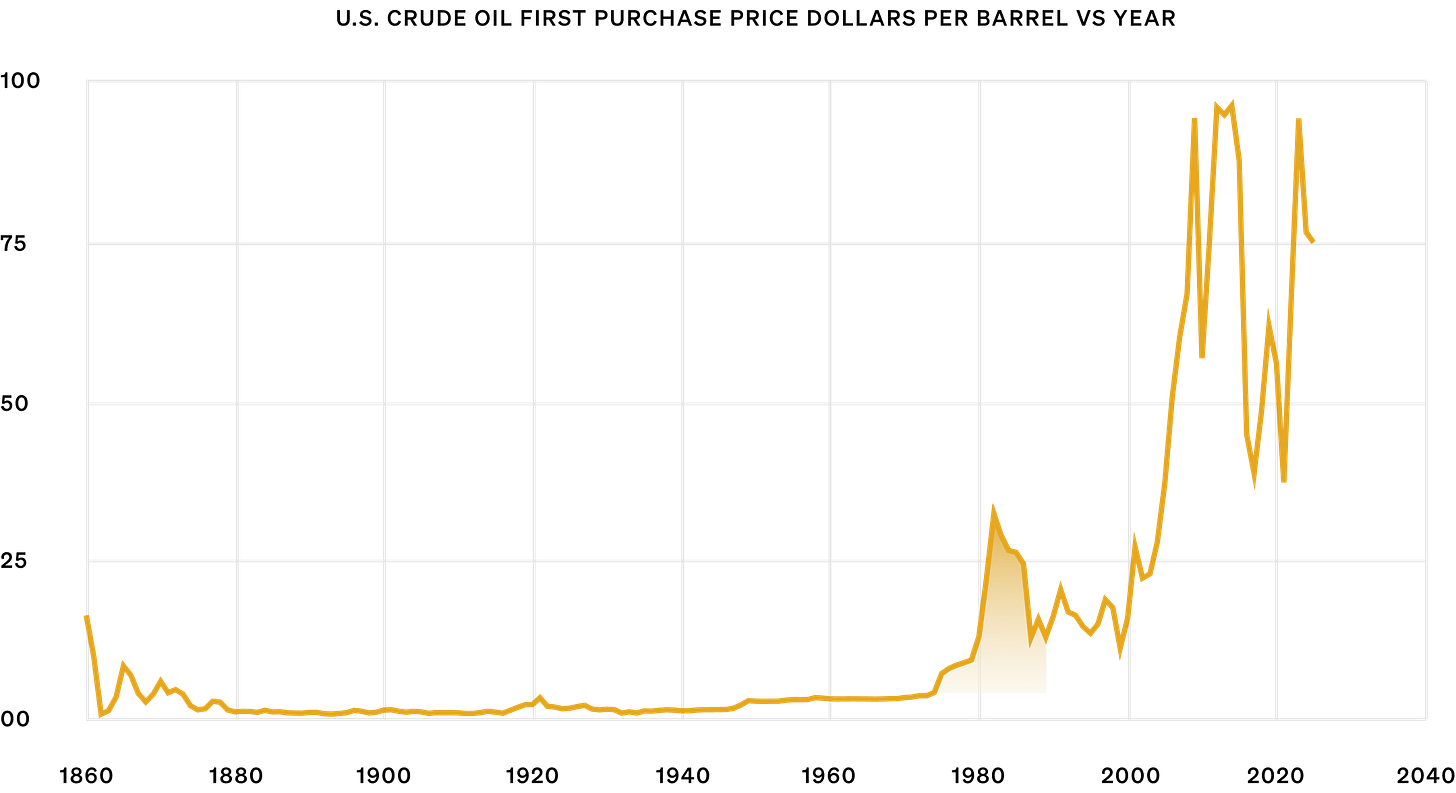

1973 Yom Kippur War (October 6–25, 1973): This war in the Middle East led OPEC countries to stop exporting oil to several Western nations. As a result, oil prices (WTI crude) jumped from about $3.50 per barrel to more than $12 per barrel by early 1974 — almost a 300 percent rise.

1979 Iranian Revolution (February 1979): The revolution in Iran caused major disruptions to oil supply. Oil prices climbed again, doubling from about $15 per barrel at the start of 1979 to more than $30 by the end of the year. They eventually peaked above $40 per barrel in 1980.

Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan (December 24, 1979): The Soviet Union’s military action increased Cold War tensions and made the global situation even more unstable. Each of these events created fear and uncertainty for investors.

Gold, which has long been considered a safe place to store value during times of crisis, became even more attractive.

This meant that beyond inflation, the geopolitical chaos of the 1970s gave investors a strong additional reason to buy gold.

Trust in U.S. Dollar Erodes (Early De-Dollarization):

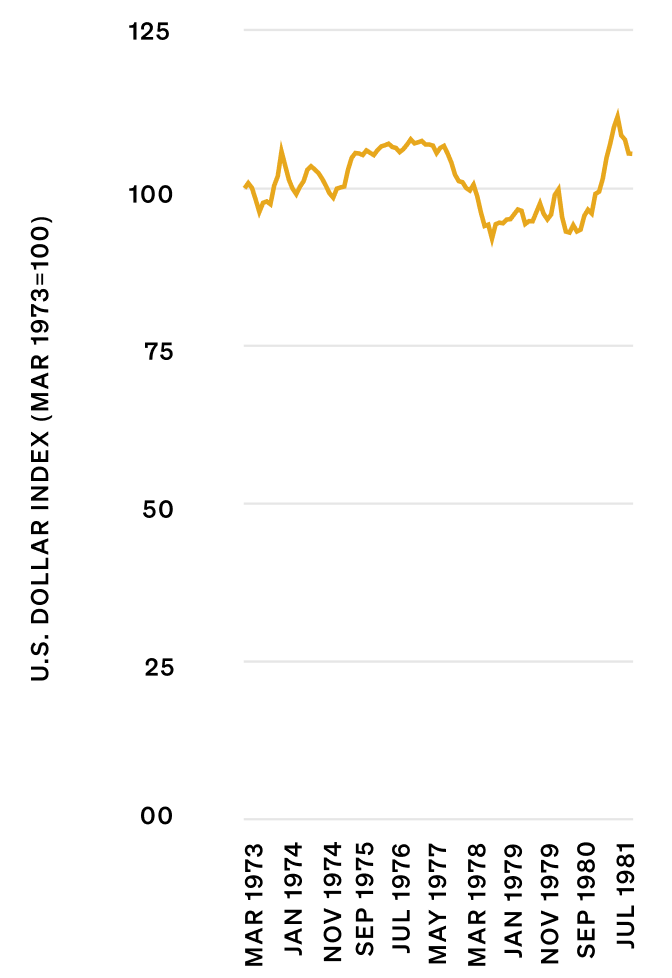

By the late 1970s, the U.S. dollar had weakened dramatically. The combination of high inflation, two oil shocks, and the end of the gold standard had shaken faith in the currency

In 1978–79, the situation became so serious that it was referred to as a “dollar crisis.” Investors were losing confidence in the dollar’s ability to hold its value. To attract foreign investors, the U.S. had to issue bonds in other currencies, known as Carter bonds.

For context, the Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index, which tracks the dollar’s value against a basket of major trading partners, fell by more than 20% compared to its 1971 level. It hit a low point of about 81.16 in October 1978 — one of the weakest levels for the dollar in that era.

This weakness did not go unnoticed internationally. Many countries, including oil-rich nations, began to diversify their reserves. Instead of holding only U.S. dollars, they started buying more gold, seeing it as a neutral and safer store of value.

This marked the early phase of de-dollarization. It was not a total rejection of the dollar, but it clearly showed a loss of trust in its long-term stability. Gold once again became the preferred choice for central banks and investors seeking monetary safety.

1970s followed the same core pattern seen in earlier periods. A major monetary shift, the end of the gold standard, combined with soaring inflation, geopolitical crises, and a weakening dollar to create the perfect conditions for gold to surge

.

Highly indebted to team groww for providing such in-depth research.