Wherever we see people around a street-corner paan shop. We mostly see people having chai. But with that chai we also see them holding a thin white stick with a glowing tip.

Cigarettes.

A product known for causing serious health problems. Yet paradoxically, it has also built one of the strongest and most durable business empires in India.

Seven out of ten times, when the shopkeeper reaches under the counter and pulls out a cigarette pack, what he hands over is made by a single company.

This moment repeats itself millions of times every single day across India, quietly generating a large share of profits for that one company.

ITC.

Before going any further, one thing needs to be stated clearly.

Cigarettes are harmful. Smoking is addictive and causes serious health damage. In India alone, over a million deaths every year are linked to smoking, and the economic cost of tobacco-related illness runs into tens of billions of dollars annually.

This is why cigarettes are among the most tightly regulated consumer products in the country. If there is an industry the state has actively tried to discourage, this is it.

And yet, ITC has somehow managed to be a leader in this industry.

98% of India’s legal cigarette sales come from the top four players:

ITC, Godfrey Phillips, VST Industries, and brands sold under Philip Morris licences.

And ITC alone accounts for more than 70% of this market.

The tobacco industry in India is huge compared to other countries in the world. It employed some 7 million people during 2004-05, accounting for 1.5% of overall employment.

To understand how ITC built this dominance in this industry, it’s important to understand the structure of the market it operates in and consider the nature of the product it sells.

Cigarettes are not like soaps or biscuits.

You can’t advertise them, promote them openly, and you can’t even clearly display the brand on the pack.

So how did ITC become so big in an industry that is constantly being restricted, taxed, and discouraged?

This report explores how ITC started building its moat and why competitors struggle to breach its “invisible wall” of competitive advantage.

History

The story starts in 1910, when a British company called the Imperial Tobacco Company of India partnered with Indian tobacco farmers and set up its first cigarette factory by 1913.

At a time when the cigarette market in India was still nascent and competition was minimal, ITC got a head start in sourcing, manufacturing, and scale, long before serious competition existed.

Over the next few decades, ITC acquired rival factories, built its own specialty paper and packaging units, and reduced dependence on imports.

Step by step, it built the entire cigarette value chain.

By the time India became independent, ITC already controlled most of the organised cigarette market. Brands owned by ITC were already household names.

Regulation: Rules ended up protecting ITC

Many of the laws meant to reduce smoking have unintentionally strengthened ITC’s position.

Instead of creating competition, regulation has made it harder for anyone new to enter.

The biggest barrier is the advertising ban.

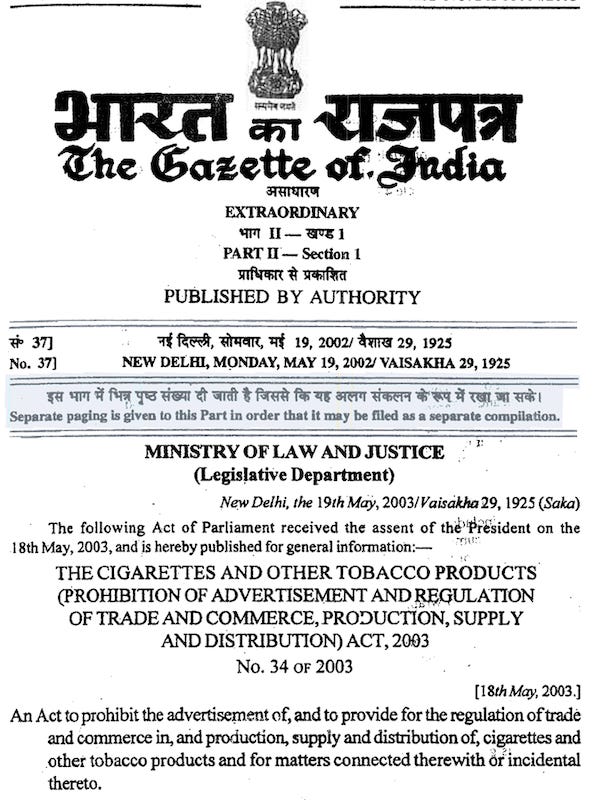

In the early 2000s, India introduced stringent tobacco control measures: a comprehensive advertising ban (under the 2003 COTPA law), severe health warning requirements on packs, and ever-increasing excise taxes on cigarettes.

Since then, cigarette companies are not allowed to advertise, sponsor events, or promote their brands in public. For a new player, this is crippling.

However, ITC had already built its brands over decades when advertising was allowed. Smokers already recognise its packs and names. So while the door was slammed shut for newcomers, ITC was already inside.

Manufacturing rules add another layer of protection.

Cigarette production has long been tightly licensed in India. Setting up a factory isn’t just a business decision. It requires government approval, which has historically been limited and difficult to obtain. ITC already had its factories and licences in place long before these restrictions hardened.

As a result, no meaningful new domestic cigarette manufacturer has emerged in decades. The industry has remained frozen with the same few old players, and ITC remains the largest among them.

India’s foreign investment policy quietly reinforced ITC’s dominance as well.

Since 2010, the government has completely banned FDI in cigarette manufacturing. That single rule changed the competitive landscape.

Global tobacco majors like Philip Morris or Japan Tobacco cannot set up their own factories in India. At best, they can operate through minority stakes or licensing arrangements with Indian companies.

This restriction directly limited foreign threats. British American Tobacco (BAT), which has historically held close to a 30% stake in ITC, was prevented from increasing its control.

Because of this, global brands never became real challengers. Marlboro, despite its global prestige, is sold in India only through a licensing arrangement with Godfrey Phillips, without full-scale investment or distribution muscle.

BAT remains a passive shareholder rather than an aggressive competitor. In effect, policy walls insulated ITC from global giants, allowing it to lock in its home-market advantage with little external disruption.

India puts very high taxes and strict health rules on cigarettes. There are heavy excise duties, GST, extra cesses, and large health warnings on every pack. These rules apply to everyone, but big players handle them much better than small ones.

Because taxes are so high, all cigarette brands end up being expensive. A new company cannot sell much cheaper than ITC, because taxes leave very little room to cut prices. If they try, they lose money. ITC’s large scale helps it absorb these costs comfortably.

Put together, regulation acts like a wall around the industry.

Brand Depth and Smoker Loyalty

ITC’s biggest advantage in cigarettes comes from time.

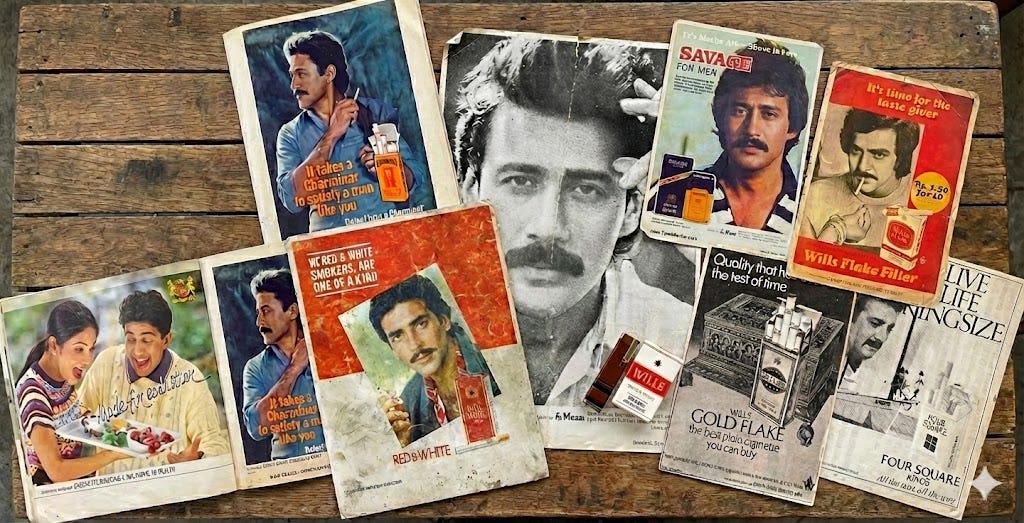

Being in the business for over a century allowed it to build brands when advertising was legal, visible, and powerful. Cigarette consumption is habit-driven, and smokers usually stick to the same taste, same feeling, and same brand for years.

ITC used this window early on to plant brands deep in consumer memory.

Names like Gold Flake, Wills Navy Cut, Classic, Scissors, Capstan, Berkeley, and others have been in the market for generations.

As a result, ITC built trust and familiarity among consumers.

Smokers mostly stick to a brand throughout their smoking span. It’s not just the smoking they are used to but also the taste/feeling of a particular brand.

Even if a new competitor enters with a new cigarette, convincing smokers to switch from their preferred ITC brand would be very difficult, especially since advertising is banned.

ITC products became familiar long before restrictions arrived, helped by aggressive marketing and cultural associations such as sports sponsorships.

Once advertising was banned, these brands didn’t need promotion anymore, they were already remembered.

Not just the different brands; over time, ITC strategically developed brands at all price levels.

For budget-conscious smokers, it has value brands (e.g. Scissors, Bristol); for mainstream smokers, mid-range brands (Wills Navy Cut, Gold Flake); and for premium customers, elite brands (Classic, Insignia, India Kings).

Having a brand at each tier means ITC can capture customers up the value chain and prevent competitors from finding a niche.

For example, if a rival focuses on low-end cheap cigarettes, ITC already has offerings there; if they try a premium segment, ITC’s is also here.

Distribution

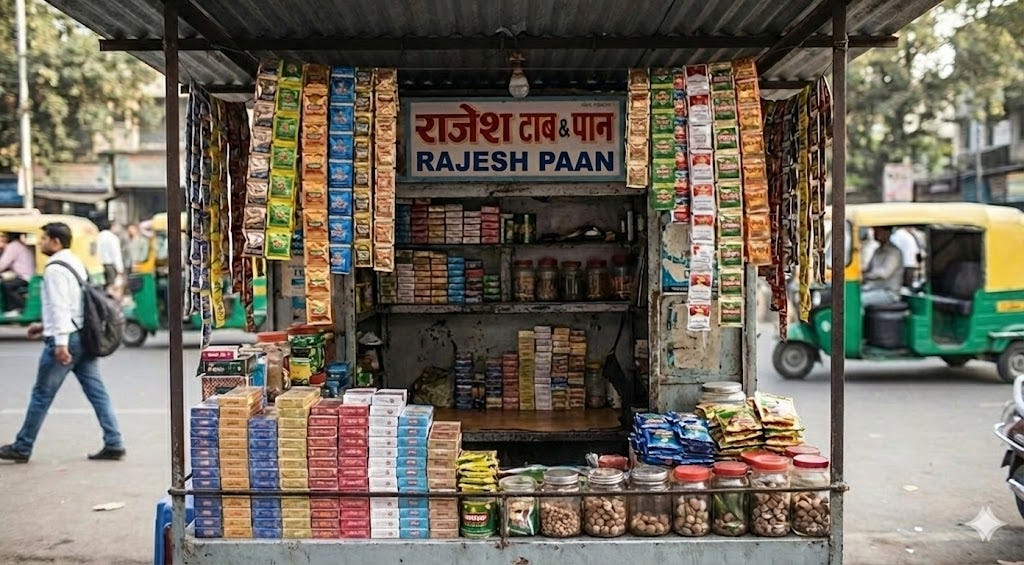

In cigarettes, distribution matters more than almost anything else. Smoking is often an impulse habit, and availability at the nearest corner shop is key.

ITC understood this early and built a distribution network that not many can match.

ITC’s cigarettes (and other products) are available in an estimated 4 million+ retail stores across India, from large city stores to the smallest roadside pan shops.

This vast last-mile network means a smoker almost anywhere in India can find an ITC cigarette brand readily. Competitors like Godfrey Phillips and VST focus on certain regions and don’t have the same depth of rural penetration.

Behind this distribution there is also a super-efficient supply chain built over decades.

ITC runs multiple manufacturing facilities across the country (at locations such as Bengaluru, Munger, Kolkata, Pune, etc.) and uses a layered distribution system that keeps shelves constantly stocked. Cigarettes are refilled often, so running out is rare.

When a smoker asks for a cigarette and ITC is always available with the retailer, the choice becomes obvious.

Over time, easy availability turns into habit, and habit turns into loyalty.

In a business where advertising is banned, what sits on the counter and what the shopkeeper reaches for over and over again matter too.

ITC’s brands are always visible at the counter, which quietly nudges smokers to choose them again and again.

This is why ITC’s dominance is about being everywhere, every day, without fail. A logistics advantage that takes years to build, and just capital alone can’t build that.

This is why distribution turned out to be its most crucial moat.

Scale, efficiency, and control of the supply chain

ITC’s cigarette business benefits enormously from scale.

Making cigarettes in very large volumes lowers the cost per unit, and ITC runs multiple large factories across the country to do exactly that.

This gives it flexibility that smaller competitors don’t have.

When taxes rise or input costs increase, ITC can adjust prices, tweak product specifications, or absorb part of the shock without hurting profitability or losing customers.

ITC has long-standing relationships with tobacco farmers and operates leaf procurement at a massive scale.

Through its agribusiness division, ITC sources leaf tobacco across roughly 17 to 22 states, handling millions of kilograms annually, part of which feeds directly into its cigarette business.

This gives a reliable supply of high-quality raw material at stable prices. This becomes a crucial advantage in a product where tobacco quality directly affects taste and cost.

ITC has also invested heavily in supply-chain efficiency, including initiatives like e-Choupal, which helped farmers connect better and helped with price transparency and procurement efficiency.

Controlling the sourcing of tobacco leaves becomes important in India, which is one of the world’s largest tobacco producers.

This scale gives ITC the financial strength.

Its cigarette profits generate large, steady cash flows that can be reinvested into better machinery, product upgrades, and research.

This in turn leads to lower production costs per cigarette than any competitor, allowing it to maintain margins even at lower price points.

Additionally, vertical integration allows ITC to innovate internally – for instance, it was the first in India to introduce capsule-filter cigarettes in some segments in response to consumer trends.

Competitors with less control over R&D or manufacturing agility would not be able to do such things.

Pricing Power and Financial Strength

One of the clearest signs of ITC’s moat is its remarkable pricing power in the cigarette industry.

Thanks to the addictive nature of nicotine and the lack of close substitutes for legal smokers, ITC can raise prices regularly without losing its core customers.

Because of this, ITC doesn’t just pass on cost increases. It often raises prices far more than the increase in taxes or input costs.

For example, in 2017, when the government increased cigarette taxes by around 2.5–6%, ITC increased retail prices by about 11–13%. Even after this big hike, sales stayed largely stable. This clearly shows how much control ITC has over pricing. Customers accepted the higher prices, which directly helped ITC earn more money.

Another reason this works is ITC’s huge market share. Since ITC controls most of the legal cigarette market, competitors don’t and can’t start price wars.

The smaller players usually follow ITC’s pricing instead of cutting prices. So profits per cigarette keep rising steadily over time.

This pricing power leads to extremely high profits. ITC’s cigarette business operates at margins of around 60% or more, which is very rare. This means a large part of the money from every cigarette sold becomes profit.

Because of these high profits, the cigarette business generates massive cash for ITC.

In FY2023-24, cigarettes made up almost 80% of the company’s total operating profit.

This cash helps ITC sustain itself through tough times ((like the quick rebound after a 5% drop in cigarette sales during COVID-19 lockdowns) and finance long-term plans that rivals without

similar profits cannot afford.

Along with this, the cigarette business requires relatively low capital investment to maintain.

In fact, ITC invested just around Rs 268 crore of incremental capital in the cigarette segment over a 10-year period, as the existing infrastructure and brands are so strong.

What makes this even stronger is that ITC doesn’t need to spend much money to keep this business running. The factories, brands, and distribution are already built. So the cigarette business keeps producing cash year after year with very little extra investment.

Basically, ITC’s pricing power ensures high margins, and its financial strength (high cash generation and reserves) forms a moat by enabling it to out-invest and outlast any challenger.

It can absorb tax increases, regulatory costs, or economic downturns far better than others, all while maintaining robust profitability.

With over 70% share of India’s legal cigarette market, ITC enjoys exceptional pricing power, ultra-high margins, and steady cash flows that are extremely difficult for any competitor to challenge.

Those cash flows become the fuel for everything else ITC does.

The rest of the portfolio (FMCG foods, paperboards & packaging, and agribusiness (and, now, its stake in ITC Hotels) expands revenues, diversifies risk, and keeps the company relevant over the long term. But none of these comes close to cigarettes in operating profit contribution.

In effect, cigarettes cigarettes effectively bankroll the wider ecosystem, funding FMCG investments, absorbing cyclicality elsewhere, and giving ITC unusual patience in capital allocation.

As long as cigarettes remain legal in India, ITC’s fortress is unlikely to crack and the cash from that single product will continue to quietly power the rest of the company.